SPECIES INFO

This pair of Morphos is confusing. Although it might be Morpho peleides, it is too far south for that name. Although it might be bristowi, it is too far east for that name.

Oscar Rojas was somewhat of a Frank Buck collector. He lived in Gigantae, Huila, Colombia which is near the Ecuador border and collected locally. Furthermore, he occasionally purchased specimens from travelers from the Putumayo Valley. How far down in the valley is unknown. We purchased specimens directly from Mr. Rojas in the time era of about 1970-1975.

The male has been digitally repaired. One rear wing was missing a big chunk. However, by copying the other side and flipping and then pasting, a nice image resulted.We have created an arbitrary genus to help explain the various subspecies of the Morpho helenor and Morpho achilles group that are found on the mainland of South America.

According to recent taxonomy of both Gerardo Lamas and Patrick Blandin there are a very large number of subspecies in the Morpho helenor group, perhaps a total of 30 or more. There are also about 8 recognized subspecies in the Morpho achilles group. We felt that by separating the species in these two genera that are found in Central America, we could held facilitate accurate identification.

The Morpho helenor group can be easily separated from the Morpho achilles group by noting that the Morpho helenor group has a rounded corner in the outer corner of the rear wing. Morpho achilles has a much sharper corner in the same place. This is very evident when studying the pattern on the underside of the rear wing.

As an amateur taxonomist we give LeMoult and Real a grade A+ for their research and making a very thorough analyses of understanding the taxonomy of these two genera. We also give Patrick Blandin a grade a+ for his further and detailed analyses.

However, we note that several serious problem potentially remain:

1) Le Moult and Real separated the Morpho helenor group in several different sections. Should these be included in the taxonomy?

2) This writer has a hard time accepting the fact that a Morpho lifeform found in the dry areas of western Mexico can be the same species as one found in either the lowland Amazon rainforest or the higher Andes Mountains. Food plants, weather cycles, humidity, and other factors would indicate that the Morpho helenor group contains more than one or two full species.

In some instances in the icons in this group we have used the Le Moult names.

Le Moult and Real in 1962 listed the following seven species in this group:

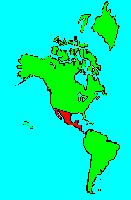

Morpho peleides - Colombia to Ecuador

Morpho marinita - Costa Rica and Panama

Morpho montezuma - Mexico to Panama

Morpho octavia - Guatemala to Panama

Morpho hyacinthus - Mexico to Panama

Morpho corydon - Colombia and Venezuela

Morpho confusa - Colombia

Gerardo Lamas in his 2004 checklist moves all of these to subspecies of Morpho helenor and adds as follows:

Morpho cortone - Colombia (Formelry in M. peleides)

Morpho corydon - Venezuela

Morpho guerrerensis - West Mexico (Formerly in M.hyacinthus)

Morpho maculata - Ecuador (Formerly in M. peleides)

Morpho marinita - Costa Rica and Panama

Morpho montezuma - Mexico to Honduras

Morpho narcissus - Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama

Morpho octavia - Mexico (Chiapas), Guatemala, El Salvador

Morpho peleus(?) - Venezuela

Morpho telemon - Colombia

Morpho tucipita - Venezuela

Morpho ululina - Venezuela

Morpho zonaras - Panama (Formerly in M. octavia)

However, the large amount of material that came across my desk from south western Costa Rica (near the Panama border) caused me and several others to totally rethink either of these organizations. If one assumes if lifeforms co-exist at the same place without intermediate forms commonly present, then there are at least five species in the so-called peleides group in this material from Golfeto, Costa Rica.

Additionally, large amounts of material in the same group from northern El Salvador also arrived here. Again, if two lifeforms fly in the same place yet keep major differences in appearance, then they should be full species in their own right.

We are not suggesting the following opinions deserve revision status, but we do point out that serious research into the definition of "species" in light of all this Central America material is in order.

Morpho butterflies (Family Morphodae to Subfamily Morphiinae) are characterized by their large size and brilliant blue colors. They typically have small bodies and fly with a floating or soaring style. They are found only in the American tropics from Mexico to Southern Brazil.

Because of the brilliant blue colors, large size, and beautiful patterns, many species of these Morphos were used for art work projects from l930 to l990. Cities such as Tingo Maria (Peru), Obidos (Brazil), Santa Catarina (Brazil), and Muzo (Colombia) had networks of collectors that exported large quantities of these beautiful butterflies. Fortunately, the reproductive powers of these species were great, and the collecting seems to have had little impact on the quantity in nature. However, land clearing projects in the natural habitats will impact their populations.

This group's taxonomy is very complicated. For extensive information refer to the Le Moult and Real revision of "Les Morpho D'Amerique Du Sud Et Centrale" published by Le Moult in l962. Prior to this Le Moult revision, there were hundreds of different named forms. Le Moult reduced the species to less than 80 species, and showed that there are some cases of convergent evolution in the family and some surprising mimicry pairs.

LeMoult's work includes 672 images of which 144 are in color. Included in these 672 images are over 600 images of types. (Types are the specimens that were used when the species was first described.)

Le Moult's work has not generally been accepted by the lepidopterists community. This is no doubt partially because it is in French, and partially because the taxonomy is so complicated that many people do not have the patience to unravel the complicated problems. However, the serious butterfly student will be really rewarded when he can understand that Morpho achilles and Morpho helenor are really a mimicry pair and not sibling species.

Morphos are divided into several different subgenera. The subgenus name is used in several instances as opposed to the common term "Morpho."

We have followed the LeMoult organization, as that places similar species near each other. (When working with an alphabetical list, this complicated group gets even more complicated.)

Since 1962 when LeMoult and Real published their revision, there has been considerable additional research. We have noted the changes using the Gerardo Lamas Checklist as published in 2004. These changes are noted in the text for each subgenera. We are impressed with the inclusion in the Lamas check list of over 8 pages of Morpho synonyms with both author and date making this a very important work. Mr. Lamas notes that his personal collection and research from Patrick Blandin and others have helped in his organization.

Then Patrick Blandin published his excellent work on the Morphos. He has color pictures of almost all males, and most of the females.

Additionally, Morpho athena was described in 1966 from RJ, Brazil. Additionally, Morpho absolini has become a full species.

Butterflies and Moths (Order Lepidoptera) are a group of insects with four large wings. They go through various life cycles including eggs, caterpillar (larvae), pupae, and adult. Most butterflies and moths feed as adults, but primarily do most of their growing in the larval or caterpillar stage. Also, most species are restricted to feeding as caterpillars upon a unique set of plants. In this pairing of insects to plants, there arises a unique plant population control system. When one plant species becomes too common, specific pests to that species also become more common and thus prevent the further spreading of that particular plant species.

Although most people think of the Lepidoptera as two different groups: butterflies and moths, technically, the concept is not valid.

Some families, such as Silk Moths (Saturnidae) and Hawk Moths (Sphingidae), are clearly moths. Other families, such as Swallowtail Butterflies (Papilionidae), are clearly butterflies, However, several families exhibit characteristics that appear to be neither moths nor butterflies. For example: the Castnia Moths of South America are frequently placed in the Skipper Family (Hesperidae). The Sunset Moths (Uranidae) have long narrow antennae and fly during the day.

The Saturnidae (Silk Moths) and Papilionidae (Swallowtails) are two Lepidoptera families that have been very carefully researched as to species and subspecies. The current thinking is that if the male genitalia are alike, then the two specimens belong to the same species. As an amateur, your editor disagrees with this premise. If the genitalia are different, then no doubt two species are involved. However, if the genitalia are alike, it only proves that the genitalia are alike.

Consider Papilio multicaudata which is found in southern Canada at higher altitudes. Papilio multicaudata is found south through the Rocky Mountains as far south as Mexico City, and recently as far south as Guatemala. With different food plants, different soil types, different climates, and different seasonal patterns, it is hard to believe that this complex is all one species.

Consider capturing 100 living individuals at any life stage in Guatemala and then carrying them north to southern Canada. Would these individuals survive through several generations. If they would not survive, then this author would conclude that two different species are involved!

In the Saturnidae consider Eacles imperialis subspecies pini. This life form feeds on pines. Is not this sufficient to justify a full species status?

Note: Numerous museums and biologists have loaned specimens to be photographed for this project.

Insects (Class Insecta) are the most successful animals on Earth if success is measured by the number of species or the total number of living organisms. This class contains more than a million species, of which North America has approximately 100,000. (Recent estimates place the number of worldwide species at four to six million.)

Insects have an exoskeleton. The body is divided into three parts. The foremost part, the head, usually bears two antennae. The middle part, the thorax, has six legs and usually four wings. The last part, the abdomen, is used for breathing and reproduction.

Although different taxonomists divide the insects differently, about thirty-five different orders are included in most of the systems.

The following abbreviated list identifies some common orders of the many different orders of insects discussed herein:

Odonata: - Dragon and Damsel Flies

Orthoptera: - Grasshoppers and Mantids

Homoptera: - Cicadas and Misc. Hoppers

Diptera: - Flies and Mosquitoes

Hymenoptera: - Ants, Wasps, and Bees

Lepidoptera: - Butterflies and Moths

Coleoptera: - Beetles

Jointed Legged Animals (Phylum Arthropoda) make up the largest phylum. There are probably more than one million different species of arthropods known to science. It is also the most successful animal phylum in terms of the total number of living organisms.

Butterflies, beetles, grasshoppers, various insects, spiders, and crabs are well-known arthropods.

The phylum is usually broken into the following five main classes:

Arachnida: - Spiders and Scorpions

Crustacea: - Crabs and Crayfish

Chilopoda: - Centipedes

Diplopoda: - Millipedes

Insecta: - Insects

There are several other "rare" classes in the arthropods that should be mentioned. A more formal list is as follows:

Sub Phylum Chelicerata

C. Arachnida: - Spiders and scorpions

C. Pycnogonida: - Sea spiders (500 species)

C. Merostomata: - Mostly fossil species

Sub Phylum Mandibulata

C. Crustacea: - Crabs and crayfish

Myriapod Group

C. Chilopoda: - Centipedes

C. Diplopoda: - Millipedes

C. Pauropoda: - Tiny millipede-like

C. Symphyla: - Garden centipedes

Insect Group

C. Insecta: - Insects

The above list does not include some extinct classes of Arthropods such as the Trilobites.

Animal Kingdom contains numerous organisms that feed on other animals or plants. Included in the animal kingdom are the lower marine invertebrates such as sponges and corals, the jointed legged animals such as insects and spiders, and the backboned animals such as fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.