SPECIES INFO

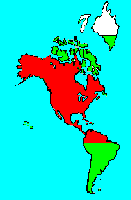

The species Papilio polyxenes and its relatives are found from southern Canada to the Caribbean and south through Mexico through parts of Central America to the highlands of Colombia and even as far south as northern Peru.

When Rothschild and Jordan published their revision of the New World Papilionidae in 1906, they listed the following subspecies:

Papilio polyxenes americus: North Peru, Colombia, and Venezuela.

Papilio polyxenes stabilis: Costa Rica and Panama

Papilio polyxenes asterius: Canada to Honduras

Papilio polyxenes polyxenes: Cuba

Papilio polyxenes brevicauda: New Foundland (Now a full species)

This writer can not accept that a lifeform that can live through the harsh winters of Canada is the same lifeform that is found in the tropics of Cuba. The genetics involving food plants, life cycle timing, resistance to certain temperatures, and resistance to certain diseases must be quite different.

We are becoming convinced that most of the above subspecies should receive full species status. We are slowly becoming convinced that the lifeforms from Arizona, east Mexico including Veracruz, and SW Mexico including Guerrero should also be considered full lifeforms.

However, in order to help facilitate study of the Papilio polyxenes complex, we are going to list all these lifeforms as subspecies of Papilio polyxenes, and also indicate the subspecies by their geographic origin. (The only exception will be noting that the form Papilio pseudoamericus of Arizona as a full species, as once that was considered by Holland as a full species.)

Papilio polyxenes was originally described from Cuba. Consequently, the lifeform Papilio polyxenes polyxenes is native to Cuba. Careful reading of the Rothschild and Jordan 1906 revision of the American Papilios notes this lifeform came from South American Islands, and R and J presumed that referred to Cuba. However, an additional comment from R and J under Papilio polyxenes polyxenes implies this form is also found in North America. (Presumably some parts of Florida.)

In the Collins Field Guide to the Butterflies of the West Indies by Norman Riley published in 1975, they picture Papilio polyxenes polyxenes with a wide yellow dorsal band in the rear wing entering the cell. They note this can be found in Cuba especially near Habana. In Tyler, Brown, and Wilson published in 1994, they show males also with a rear wing band entering the cell.

Herewith we show a males from Andros Island. Andros is in the Bahamas just east of Miami, Florida, and extending south near Cuba.

Before concluding a discussion of the various lifeforms in this complex, we also need to review the definition of a species. Generally, something along these lines appears to be accepted. "Two life forms that can reproduce viable fertile offspring can be considered to represent the same species." We feel, at least for insects, an additional phrase can be added to this definition: "that can survive in the habitat of either parent" Then, the concept of a "subspecies" can be defined as different geographical groups of the same species that can easily separated from each other by physical characteristics.

The next concept relates to "forms". Forms are different appearing representatives of a species that can appear within a given species or subspecies. Examples of forms can include: Male-Female in most animals, telodont and amphidont in the Lucanidae (Odontolabis) beetles, and in butterflies our common yellow alfalfa butterfly, Colias philodice, will produce "white" females. And, of course, the common North American yellow and black Papilio glaucus swallowtail can produce blue females.

When we consider the wide range of environments that currently support Papilio polyxenes per the organization of Gerardo Lamas in 2004, we find we must suggest another organization.

Per the Lamas organization a species that survives in southern Canada is the same species that survives in Colombia, South America. We immediately separate out Papilio brevicauda, kahli, nitra, rudkini, and bairdi, and Papilio zelicaon as probable full species.

Then we create several groups of the remaining Papilio polyxenes based on their geographic range. Although we will present discussion that many of the subspecies in these groups should achieve full species status, we at least will have them grouped by geography.

The groups are as follows:

Papilio polyxenes polyxenes - Cuba, Bahamas and maybe south Florida

The remaining groups are arranged starting first with east Canada and south towards Florida and then west to the Great Plains, then further west to the Rocky Mountains, and then further west to the West Coast. Then south to California, Mexico, central Central America, Colombia and south.

Papilio brevicauda - East Canada

Papilio polyxenes asterius - East USA to Great Plains

Papilio polyxenes - Great Plains

Papilio polyxenes - Rocky Mountains

Papilio polyxenes - West Coast of the United States

Papilio polyxenes - Mexico

Papilio polyxenes - Central America

Papilio polyxenes - Colombia and Peru

However, when we study Hamilton Tyler and is Butterflies of the Americas, we note that many of the Canadian and northern USA life forms have been moved into the Papilio machaon complex.New World Papilio machaon group is in a state of taxonomic confusion. The thinking used here is that Papilio polyxenes is found from New England to southern Colombia. However, the western United States and Canadian forms of this complex group have been divided into many different species. There is no doubt that the thinking will change as breeding experiments are conducted.

When Rothschild and Jordan revised the New World Papilionidae they listed only six species in this group. However, six of the various subspecies have been raised to full species status.

Papilio brevicauda used to be considered a subspecies of Papilio polyxenes. Papilio gothica was a mountain form of Papilio zelicaon. Papilio rudkini was a desert form of Papilio zelicaon.

Papilio joanae is a new discovery from southern Missouri that is closely related to Papilio polyxenes. Papilio oregonius is a form from the Pacific Northwest related to Papilio machaon. Papilio kahli is very close to Papilio polyxenes and Papilio machaon. The species are (an * indicates that this species is pictured):

SPECIES - - - - - - LOCATION

Papilio brevicauda* - East Canada

Papilio kahli* - Central-West Canada

Papilio oregonius* - West Canada and northwest USA

Papilio gothica* - Rocky Mountains of USA

Papilio joanae* - Ozarks of south Missouri of USA

Papilio polyxenes* - East USA to Colombia

Papilio bairdi* - West USA

Papilio rudkini* - Deserts of southwest USA

Papilio zelicaon* - mostly California

Papilio indra* - mostly mountains of west USA

Papilio machaon* - North Canada (and Old World)

Papilio nitra* - Alberta Canada to Colorado

Family Papilionidae (Swallowtails), Papilio family, contains about five hundred and fifty different species with perhaps a new species still being discovered every two or three years. Many species are sexually dimorphic in that the females do not look like the males. A common example of this is the Tiger Swallowtail of North America where the males are always yellow and black and the females can be either yellow and black or occasionally a blue color.

Swallowtails are usually medium to large species and strong fliers. They are unusual in that the adults have six fully developed legs. Many newer families of butterflies have only four well-developed legs with the front two legs being very underdeveloped.

Butterfly scientists are attracted to this group, and high prices are paid for the largest and the rarest kinds. Most of the species are bred locally on a hobby-business basis to fill the demand.

The Queen Alexander might be extinct. Although this species has been protected, the damage seems to have been done by land clearing projects which took away its natural habitat. The number of specimens in collections seems to be so small that collectors cannot be blamed for this extinction. There are probably less than ten collections in the United States that have over five hundred different species of Papilionidae.

Butterflies and Moths (Order Lepidoptera) are a group of insects with four large wings. They go through various life cycles including eggs, caterpillar (larvae), pupae, and adult. Most butterflies and moths feed as adults, but primarily do most of their growing in the larval or caterpillar stage. Also, most species are restricted to feeding as caterpillars upon a unique set of plants. In this pairing of insects to plants, there arises a unique plant population control system. When one plant species becomes too common, specific pests to that species also become more common and thus prevent the further spreading of that particular plant species.

Although most people think of the Lepidoptera as two different groups: butterflies and moths, technically, the concept is not valid.

Some families, such as Silk Moths (Saturnidae) and Hawk Moths (Sphingidae), are clearly moths. Other families, such as Swallowtail Butterflies (Papilionidae), are clearly butterflies, However, several families exhibit characteristics that appear to be neither moths nor butterflies. For example: the Castnia Moths of South America are frequently placed in the Skipper Family (Hesperidae). The Sunset Moths (Uranidae) have long narrow antennae and fly during the day.

The Saturnidae (Silk Moths) and Papilionidae (Swallowtails) are two Lepidoptera families that have been very carefully researched as to species and subspecies. The current thinking is that if the male genitalia are alike, then the two specimens belong to the same species. As an amateur, your editor disagrees with this premise. If the genitalia are different, then no doubt two species are involved. However, if the genitalia are alike, it only proves that the genitalia are alike.

Consider Papilio multicaudata which is found in southern Canada at higher altitudes. Papilio multicaudata is found south through the Rocky Mountains as far south as Mexico City, and recently as far south as Guatemala. With different food plants, different soil types, different climates, and different seasonal patterns, it is hard to believe that this complex is all one species.

Consider capturing 100 living individuals at any life stage in Guatemala and then carrying them north to southern Canada. Would these individuals survive through several generations. If they would not survive, then this author would conclude that two different species are involved!

In the Saturnidae consider Eacles imperialis subspecies pini. This life form feeds on pines. Is not this sufficient to justify a full species status?

Note: Numerous museums and biologists have loaned specimens to be photographed for this project.

Insects (Class Insecta) are the most successful animals on Earth if success is measured by the number of species or the total number of living organisms. This class contains more than a million species, of which North America has approximately 100,000. (Recent estimates place the number of worldwide species at four to six million.)

Insects have an exoskeleton. The body is divided into three parts. The foremost part, the head, usually bears two antennae. The middle part, the thorax, has six legs and usually four wings. The last part, the abdomen, is used for breathing and reproduction.

Although different taxonomists divide the insects differently, about thirty-five different orders are included in most of the systems.

The following abbreviated list identifies some common orders of the many different orders of insects discussed herein:

Odonata: - Dragon and Damsel Flies

Orthoptera: - Grasshoppers and Mantids

Homoptera: - Cicadas and Misc. Hoppers

Diptera: - Flies and Mosquitoes

Hymenoptera: - Ants, Wasps, and Bees

Lepidoptera: - Butterflies and Moths

Coleoptera: - Beetles

Jointed Legged Animals (Phylum Arthropoda) make up the largest phylum. There are probably more than one million different species of arthropods known to science. It is also the most successful animal phylum in terms of the total number of living organisms.

Butterflies, beetles, grasshoppers, various insects, spiders, and crabs are well-known arthropods.

The phylum is usually broken into the following five main classes:

Arachnida: - Spiders and Scorpions

Crustacea: - Crabs and Crayfish

Chilopoda: - Centipedes

Diplopoda: - Millipedes

Insecta: - Insects

There are several other "rare" classes in the arthropods that should be mentioned. A more formal list is as follows:

Sub Phylum Chelicerata

C. Arachnida: - Spiders and scorpions

C. Pycnogonida: - Sea spiders (500 species)

C. Merostomata: - Mostly fossil species

Sub Phylum Mandibulata

C. Crustacea: - Crabs and crayfish

Myriapod Group

C. Chilopoda: - Centipedes

C. Diplopoda: - Millipedes

C. Pauropoda: - Tiny millipede-like

C. Symphyla: - Garden centipedes

Insect Group

C. Insecta: - Insects

The above list does not include some extinct classes of Arthropods such as the Trilobites.

Animal Kingdom contains numerous organisms that feed on other animals or plants. Included in the animal kingdom are the lower marine invertebrates such as sponges and corals, the jointed legged animals such as insects and spiders, and the backboned animals such as fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.